Violent Resolution: And the Rockets’ Red Glare

Pretty much any time that foes gather together in convenient lumps, someone is going to try and find a way to paste them with whatever the genre equivalent of a cluster bomb strike is. It’s only natural, really – and well supported by some historical studies. Here’s one from the World War II Databook (Table 57, p. 257):

The percentage of battle wounds to british soldiers by weapon 1939-45 overall was:

- Mortar, grenade, bomb, shell ………..75%

- Bullet, AT mine………………………10%

- mine & booby trap……………………10%

- Blast and crush…………………………2%

- Chemical………………………………2%

- other……………………………………1%

While individual battles vary (at El Alamein, I saw a note that 75% of the wounds were bullet wounds), the overall trend seemed to support the conclusion that small arms fire, by and large, held foes in place so that artillery could turn them into casualties.

While individual battles vary (at El Alamein, I saw a note that 75% of the wounds were bullet wounds), the overall trend seemed to support the conclusion that small arms fire, by and large, held foes in place so that artillery could turn them into casualties.

In some respects, this predisposes the conclusion, because on the one hand, plentiful and easy access to person-killing explosives is a thing of moderately recent history, over the last century or so (though obviously if the bombs are bursting in air, two centuries or more would be accurate as well).

The #1 genre in RPGs, though, is still epic fantasy. And epic fantasy has its own version of artillery, which is the battlefield wizard. Such characters fling pretty potent area effect spells about the landscape, either destroying foes, destroying or shifting the landscape itself, or perhaps both. More on that later.

The key bit for this segment of Violent Resolution is how well and easily do the sample games allow for one attack to impact multiple foes. And that’s what it’s really about, at the highest level – a directed attempt to inflict harm on one or more targets. Well, most of the time, since one of the original effective uses of explosives is to batter down a foe’s fortifications.

The rules for explosions in Fate can be a bit tough to find, but they’re tucked under “multiple targets” in the index, and found on p. 205 of Fate Core. As with everything, the rules are basically the same – you choose your action (Overcome an Obstacle, Create an Advantage, or Attack are the most likely here), specify which, if any, Aspects, Stunts, or Extras are being invoked, and roll.

The rules for area attacks are straightforward if broad (a descriptor which can accurately be applied to the entire system). Area attacks are adjudicated by rolling the dice as normal, and then applying the strength of the attacker’s result by distributing it to all foes that are in the area. If you happen to roll poorly, all the targets in the zone may get off scott free. If you roll very well, then you’ll likely have an intermediate to low effect on your foes, due to the requirement to split successes/margin among your targets.

As a concrete example, if you toss a grenade or sling a fireball at a group of four foes, and you have +3 in the skill and the nature of the weapon (by dint of Weapon Ratings, special defiition of an Aspect, or whatever) gives another +2, then when you attack you’ll tend to cluster around 5 shifts to divide between the four targets (basically 1 stress each, with 2 on one foe of your choice, but you could notionally put all 5 on one foe and ignore the other two). A great roll would give 9 shifts to distribute. The victims defend against the attack shifts allocated to them, not the total.

Naturally, this is modified two pages later, allowing for zone-wide attacks to be a common thing if the situation demands it.

Alternate Takes

With a nod to the Fate Fractal, one can also treat the explosive device itself as a character/aspect with its own attack skill (or weapon value) and stunts. This is the method suggested in a thread on how to handle grenades in the Fate Core Google+ community. The boom-generator is inserted into a zone, and on detonation, attacks everything in the zone, or maybe even the zone itself, with a particular skill.

Depending on the referee’s preferences, one could tag it with a Stunt that attacks with full skill on everyone in the zone individually. With the right balancing appropriate to the genre, this can be tuned to a particular effect. Massive, catastrophic damage to all in the zone (a disintegration grenade!) could be achieved by having the base attack be some ridiculously high value – 6, 8, or even 12 shifts would make short work of anyone not able to invoke the proper aspects for Cover, Armor, or Luck. A low-grade attack with only one or two skill would have a decent chance of not hurting anyone, and at best would tend to apply a few shifts of stress or consequences.

Aggressive Landscaping

The definition of everything as a character with its own aspects, stunts, etc. means that using explosives creatively does not suffer from math overload or endless page flipping. Want to blow down a wall? Decide on the attack strength of the explosive, the defensive strength of the wall, and roll it. Stress and consequences can be assigned as needed. A high-enough consequence might bring the entire building down, while a mild one might allow a free invocation of an aspect when attacking that section again. Stress instead of consequences might be cosmetic damage, such as scorched paint or blown-out windows.

The definition of everything as a character with its own aspects, stunts, etc. means that using explosives creatively does not suffer from math overload or endless page flipping. Want to blow down a wall? Decide on the attack strength of the explosive, the defensive strength of the wall, and roll it. Stress and consequences can be assigned as needed. A high-enough consequence might bring the entire building down, while a mild one might allow a free invocation of an aspect when attacking that section again. Stress instead of consequences might be cosmetic damage, such as scorched paint or blown-out windows.

The narrative bent of the game keeps the focus on what the result of the attack, advantage, or overcome action is, not how many LottaJoules of energy were in the grenade.

Arcane Explorations

There is really no difference inherent to a magical explosion as opposed to a mundane one. They’ll be treated the same way in all cases, subject to the usual variations based on Aspect, Stunt, and Extra. From that perspective, it’s handy and self-balancing. Proper choice of aspects will keep magic magical if desired.

A Sufficient Quantity of High Explosives

How does one differentiate between a hand grenade, a Javelin missile, and a small antimatter charge in Fate? Dramatically.

The mechanics support various sizes of explosions largely through the ability to either use Extras to define the strength of the attack, or to treat the exploding plot device as a character by itself. While caution should be used in assigning these values and care must be taken to keep them balanced for the style of play desired, there’s no reason not to allow scaling up the boom to reflect in-game “reality.”

Night’s Black Agents

Explosives are called out as a great equalizer in the battle against the Vampires, since there’s simply only so much that a physical body can take. Explosives up to and including a suitcase nuke are treated in the game rules.

The mechanics are geared towards personal deployment, and grenades are tossed with a difficulty set by range, such as 2 for Point Blank – which is touching range. And you’re throwing a grenade. Might want to rethink that one. But they can be thrown up to Near range (30-40m). Rifle grenades and other proper toys can reach to Long range (100m). Since the Mk 19 automatic grenade launcher can fire up to about 1,500m, allowing shots at Extended Range with the proper skills and spends isn’t out of the question.

The mechanics are geared towards personal deployment, and grenades are tossed with a difficulty set by range, such as 2 for Point Blank – which is touching range. And you’re throwing a grenade. Might want to rethink that one. But they can be thrown up to Near range (30-40m). Rifle grenades and other proper toys can reach to Long range (100m). Since the Mk 19 automatic grenade launcher can fire up to about 1,500m, allowing shots at Extended Range with the proper skills and spends isn’t out of the question.

Once you deliver the boom to the target, the explosion is figured as damage dealt based on range from the victim to the source of the blast. There are three considerations – annihilation, damage, and debris. Annihilation is just that – instant death, no saving throw, no passing go, and no collecting $200. If you’re in the damage range, you automatically take a hit, and it’s a significant one – a die of damage plus three times the explosions Class (see below). In the Debris range, you get a die roll (Athletics) to avoid the effects, but if you fail, you take a die of damage plus the explosion’s Class.

A Sufficient Quantity of High Explosives

Explosions in NBA are rated by an explosion Class, a number from 1-6. Class 1 explosions include homemade small explosives like a pipe bomb or door-busting explosive foam. Typical frag grenades are Class 2, and Class 6 is a suitcase nuke. Large explosions are possible, but are in the realm of plot device. You don’t get an annihilation range until you hit Class 3, and even then that’s only Point Blank (the RPG goes off within touching distance).

There’s an interesting bit of specificity for Class 5 explosions, which have a Damage range of Long. The only range farther than that is Extended, which is fairly arbitrary. So the book lists 240m as the debris range here. Probably a needed amplification, though an unusual one given the broad strokes that the game usually paints with.

Cover and armor are treated as an increase in effective range. If you’re behind appropriate cover you’re treated as being one range band farther away. This would need to be adjudicated with some discretion, however. Being inside a battle tank when a hand grenade goes off will probably offer total protection. The odds of being inside such armor given the genre are probably fairly low, but being behind a fortified door, castle wall, or other thick protection is probably well within the normal expectations of the thriller.

Dungeons and Dragons

The salient feature of the Wizard in the CHAINMAIL wargame was the fireball spell, and that seems to have defined spellcasters – or at least “magic users” ever since in many ways. CHAINMAIL was a wargame, to which RPG elements were derived. While spellcasters of all stripes have come a long, long way in the last 40 years of gaming, in D&D they started as a stand-in for artillery, and to some extent, that is still how they are perceived, fairly or no.

While there are many, many ways in which D&D magic users are no longer simply mildly mobile cluster artillery, for the purposes of this article, we’ll treat them within this narrow window – how to lay down the hurt on a whole group of foes at once.

Combat Lullaby

Ironically, the first time this really seems to come into play in many games is not a fireball at all. It’s the Sleep spell, which is such a staple of D&D in my experience it turns into a go-to, must-have spell in nearly all games I’ve played in (that’s a personal observation, of course). This includes the OSR-flavored Swords and Wizardry.

It’s a first-level spell, which means as soon as the caster has access to the proper spell slot (maybe starting the game for many magic-users), she can threaten creatures from 5-40 HP in value, from weakest to strongest, within a 20′ radius of the targeted point. 5d8 HP is enough to, on the average, snooze out five 1 HD creatures in the middle of a fight. Almost uniformly these slumbering foes meet inglorious ends at the sharp end of the PCs weapons after the surviving stronger monsters are dealt with. The spell scales, too, at an extra 2d8 per level of spell slot. So a 7th level spell slot will roll 19d8, even threatening fairly powerful heroes if they’re caught alone – the spell has no saving throw.

It’s not spectacular and there’s no fiery glare, but area effect spells are available right out of the gate.

Crowd Pleaser

The iconic fireball, the only spell available to the CHAINMAIL wizard at first, it too impacts a 20′ radius sphere. At its weakest (a 3rd level spell slot) it does 8d6 damage (half damage if you throw yourself out of the blast with a Dexterity save) to all creatures within that sphere, and the sphere wraps around corners, meaning cover is no protection from this magical fire. If a very high level character throws one with a 9th level spell slot, it will do 14d6 damage.

Relatively speaking, a few fireballs will play havoc with a tightly packed formation – which like their fragmentation grenade or artillery inspiration, is the entire point. Given a 1st-level character in D&D5 will have on the order of 6-14 HP, even the entry-level version can pretty much vaporize a small cluster of such fodder. Against a more potent foe, it will still be a threat. A 5HD monster might have 25-40 HP, and the damage done by the spell is 8=48 HP, which can nearly incapacitate the middling level 5HD creature even if they successfully save.

Relatively speaking, a few fireballs will play havoc with a tightly packed formation – which like their fragmentation grenade or artillery inspiration, is the entire point. Given a 1st-level character in D&D5 will have on the order of 6-14 HP, even the entry-level version can pretty much vaporize a small cluster of such fodder. Against a more potent foe, it will still be a threat. A 5HD monster might have 25-40 HP, and the damage done by the spell is 8=48 HP, which can nearly incapacitate the middling level 5HD creature even if they successfully save.

Explosive or area effect spells in D&D can get darn nasty, such as the potent Meteor Swarm – what may well be the baddest thing to hit the dungeon since TILTOWAIT. A 9th level evocation spell, it strikes everything in a 40′ sphere with 20d6 fire damage and 20d6 bludgeoning damage. It’s going to take a very, very high level fighter to not get turned into paste by that one.

That being said, a 20th level fighter (1d10 HP per level, average 6 HP) with CON 18 (+4 HP per level) has a pretty good shot at tipping the scales at 200 HP, so 40d6 total will be a mighty blow at 70 or 140 HP average, but not necessarily an automatic fight-ender. Against a high-level spellcaster, with but 1d6 HP and CON 14 or CON 16 will eke out 6-7 per level, for 120-140 HP, which is a serious threat of one-shot incapacitation. This is a deservedly powerful spell.

Magical Claymore

D&D also features directional area effect spells, such as the Cone of Cold. Doing 8d8 out of the gate and 12d8 at max power, this spell reaches out 60′ and freezes things in its path, with a width of effect equal to it’s length (it’s an equilateral triangle). This makes it intermediate in effect extent and requires some stand-off . . . and no friendly characters blocking your attack line.

Savage Worlds

This is a tactical game meant to be played with miniatures and a map. As such, the rules for using explosive and area effect attacks are built around a blast template – a usually-circular cutout that shows the size of the affected area. To toss a grenade or cast a spell into an area, one makes a skill test using the appropriate ability (Shooting, Throwing, or an appropriate spell skill all come to mind) given the range being targeted. Success means you land the template where you want it to be. Failure means it deviates randomly, and with the right flavor of flub, you can indeed be caught in your own explosion, though the rules do prevent the thing landing behind you.

Damage is by weapon or spell, and affects everyone within the blast zone at full value. There is no effect if you’re out of the zone, and as always, impacted characters are up, down, or off the table. The two grenades listed in the Deluxe rulebook do about 3d6 damage to all targets in the blast radius, which means getting caught in the blast zone is as bad as getting hit by a .50 BMG (2d10) or 14.5mm machinegun (also 3d6). That is to say: very, very nasty.

Claymore of Doom

The actual claymore antipersonnel mine makes an appearance in the rules as well, and uses the formulation for canister shot. Basically, the mine reaches out for 24″ (about 50 yds) as if the blast template slides along its entire length, impacting everything it touches for 3d6 damage. Effectively, this turns both canister and the claymore mine into a cylindrical area of effect weapon. The damage here is about right given what a claymore actually is. The shape of the effect is a bit odd – a cone effect might be a better fit.

The actual claymore antipersonnel mine makes an appearance in the rules as well, and uses the formulation for canister shot. Basically, the mine reaches out for 24″ (about 50 yds) as if the blast template slides along its entire length, impacting everything it touches for 3d6 damage. Effectively, this turns both canister and the claymore mine into a cylindrical area of effect weapon. The damage here is about right given what a claymore actually is. The shape of the effect is a bit odd – a cone effect might be a better fit.

GURPS

As one would expect based on its treatment of firearms, GURPS has a fairly detailed treatment of explosions and area effect weapons. It also allows for a bit of variation in blast effects.

Collateral Damage

GURPS assumes that explosions have a point of origin (this isn’t unique) and that the damage is strongest at the center for a “normal” explosion. Every explosion has a damage value and that only applies to the actual target struck. For everyone else, damage is rolled normally, but divided by 3x the distance in yards from the target. That means if you’re hit directly by a 6d explosion (enough to take Joe Average from fully healthy to his first death check at -HP on an average roll) you’re liable for the entire 6d, but at only 2 yards distance, you’re rolling 6d/6 (about 1d), and by the time you hit 12 yards, you’re looking at 1 point of damage at the best case, ever.

Unsurprisingly, the rules note this: the maximum impact of an explosion goes out to twice the dice of damage, in yards. That’s another way of noting the same point – X dice of damage will have a maximum roll, ever, of 6X, and damage falls off as 3D (three times the distance in yards). So for only one point of damage, you’re looking at 6X/3D = 1, or D = 2X. The math is not shown, merely stated – “an explosion inflicts ‘collateral damage’ on everything within (2 x dice of damage) yards. But you can see where it came from easily.

The blast or concussion damage, then, isn’t a big deal unless the explosion is very large or you’re very close to it. The baddest hand grenade in GURPS High-Tech (the M67) does 9d damage, which means from the blast itself you’re safe outside of 18 yards – which of course means in reality it’s impacting a sphere 36 yards in diameter, which is rather larger than the blast zone of the Meteor Swarm spell, but the zone in which you’re even liable for about 1d damage is only two yards in diameter.

That being said, the game gives you the ability to calculate the blast effects of the CBU-55/B as well, a 500-lb fuel-air explosive bomb which detonates for 6dx65 damage – 390 dice, which means you need to be 780 yards away – over 0.4 miles – before you’re truly safe. And yes, this can scale up to nuclear weapons if desired: the “Little Boy” bomb released over Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945, hit with roughly the force of 12,500 tons of TNT, or 60,000 dice of damage, with a linked burning damage (due to the flash) of 6dx6,500 burn ex.

Flash, Ah-ah! and the Rain of Pain

As noted in the nuclear example above, there are many types of explosions and properties. Electromagnetic pulse, a thermal blast, shaped charges, and fragmentation damage can all be modeled accurately if desired.

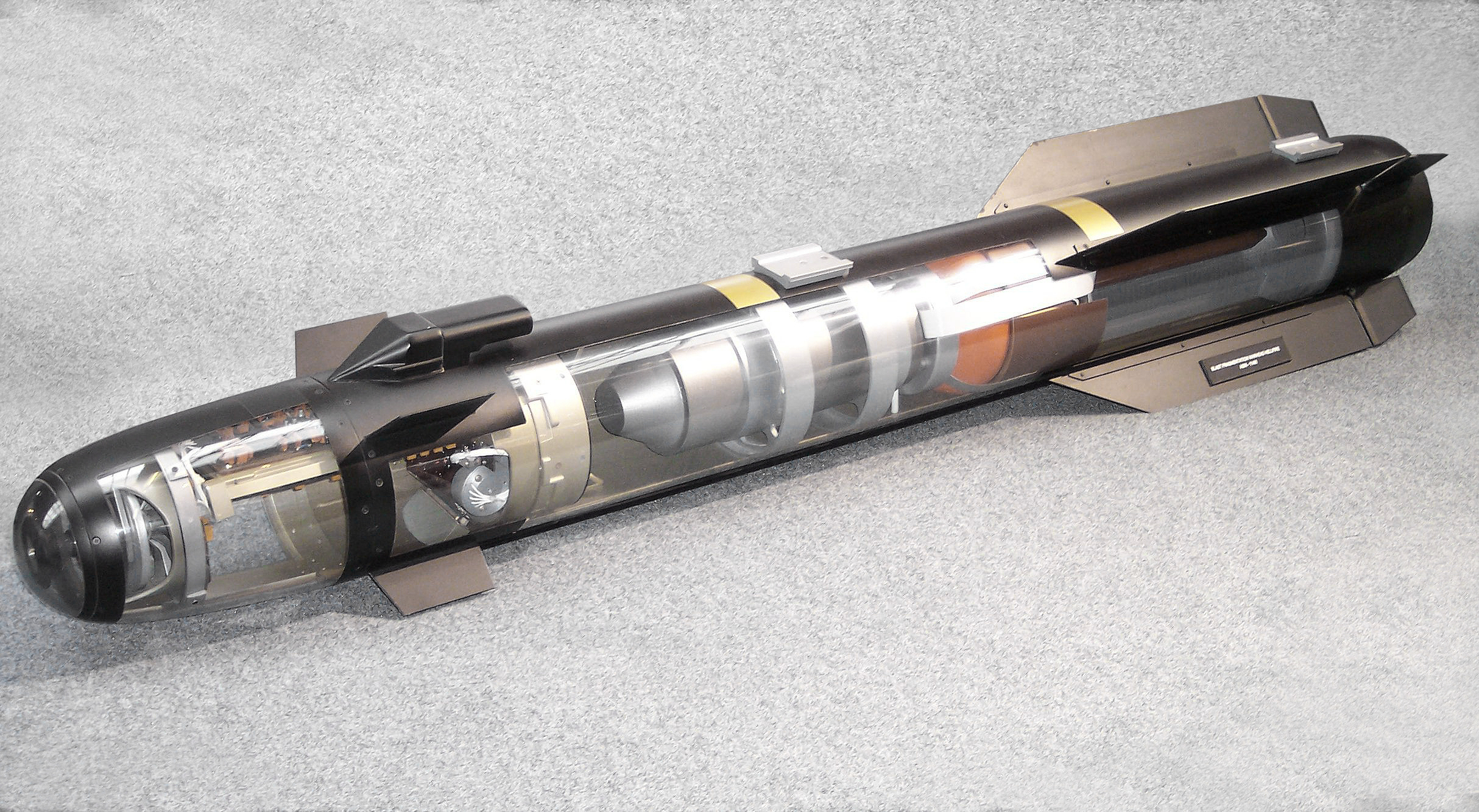

This isn’t necessarily just fluff, either. A Hellfire missile (AGM-114) carries a warhead of “only” 20-lbs of explosives, which detonate with the force of about 23 lbs. of TNT. That’s about 60d worth of damage (call it 6dx10), which will do but 1d damage past 20 yards, and by itself won’t hardly scratch the paint on a modern tank glacis. But with the shaped charge rules, which divide armor by 10, penetration is more like 600d, enough to worry you if you’re behind less than 30″ of RHA steel, or 380mm of laminate armor.

The other critical piece is that modern antipersonnel weaponry doesn’t blow you apart as the primary method of destruction – it’s the fragments that get you. Each weapon that generates fragments damages out to 5x the dice of damage of the frag attack (the aforementioned M67 does 2d fragmentation, and is thus dangerous to 10 yds. The Mk 82 500-lb HE bomb does 14d fragmentation, and is thus dangerous to 70 yards). The fragmentation attack is an autofire weapons attack, throwing random fragments out with Skill-15. This is modified only by range, target size, and target posture, and it’s possible to get tagged in various places in one burst.

Nerf Magic

Direct damage spells using the standard GURPS Magic rules, which treat spells as learnable skills powered by fatigue points, are relatively weak compared to their high-fantasy ancestors. While supplements such as the ever-expanding Dungeon Fantasy line can up-gun this a bit, the fall-off of damage with distance means that even a 6d fireball (which in GURPS is basically a contact-only spell) turned into an explosive fireball will mostly be a point or so of damage past about two yards.

Not that GURPS mages can’t do nasty things to folks – it’s just that nasty is things like Create Fire and Fire Cloud – both relatively low-damage per second, but good for controlling movement on the battlefield, rather than laying waste to swarms of foes. Likewise Grease or Ice Slick don’t do damage but basically makes you roll vs DX-2 every time you look at something funny, or else fall down.

Not that GURPS mages can’t do nasty things to folks – it’s just that nasty is things like Create Fire and Fire Cloud – both relatively low-damage per second, but good for controlling movement on the battlefield, rather than laying waste to swarms of foes. Likewise Grease or Ice Slick don’t do damage but basically makes you roll vs DX-2 every time you look at something funny, or else fall down.

There are other magic systems that can be brought to bear if you want a more battlefield-style magic, as well as area-effect Innate Attacks and other things that go boom. But as written, and using the rules for explosions, it is both difficult and expensive to do something like Meteor Swarm in GURPS (though they don’t map well – a 3d attack is a borderline incapacitating one in GURPS against an average human; 6d is, on the average, lethal. You don’t need a 40d attack to smack down high point value humans in GURPS; 6-10d will usually do).

Human Artillery

Whether equipment is driving the boom factor or if it’s powered by magic, area effect and explosions are heady stuff. Some players make a rule of clustering into formation, with a definite marching order and a standard operating procedure of forming ranks against foes. As in life, this has advantages and disadvantages. In the tactically-focused games (GURPS, D&D, Savage Worlds) the benefits include denying attacks at the back rows (enabling archers and casters to do their thing in relative peace), allowing concentration of force and defenses, and where it matters, preventing being outflanked piecemeal.

On the down side, that many targets in once place is tailor-made to draw area-effect spells. I know of at least one player who would have a hard time not hitting his own party with a fireball given that many targets in proximity. It’s just too tempting to pass up.

More seriously, area effects make for a good tension and can provide some beneficial choices within a party. Cluster all together and risk being taken out all at once, or split into several separated groups, which can be attacked and overwhelmed bit by bit?

The narrative games each have relatively solid mechanics for explosives, but the GM will need to adjudicate who’s in range and who’s immune each time given the abstract nature of the systems involved. This is offset by the basis of the games being to make the characters look good. The various things that can be done with Fate (Create an Advantage and Attack) could easily be used in a straightforward manner to represent Rated G or Rated PG combat, where a grenade might toss you around or knock you out, but won’t leave you a bleeding wreck with the application of a suitable aspect.

This last weekend marked the Fourth of July. Since I’m an American, we celebrated by detonating vast quantities of explosives – this provided the inspiration for the title and timing of this piece. So with that, I’ll cherry-pick an RPG-suitable closing stanza from Key’s original poem. Poor hirelings; they always get the short end:

And where is that band who so vauntingly sworeThat the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

Good piece! While I was working on my Bradley article, I'd started picking through explosive weapons again. Fortunately, everything I needed was in High Tech this time, but that wont be the case when I go to do a couple others I have in mind.

Interesting that you put magic and tech side by side. One of my various concept campaigns involved a universe much like the modern day that had been taken over by mages (Illuminati, basically). Players would have been mundane special forces operators, with the exception of an Academy Representative – essentially a battle-mage/soldier/propagandist hybrid. Most spells do look rather anemic next to modern powers; mostly the direct damage ones.

Cheers!

Don't forget the incidental fragmentation rules in GURPS. Even that Explosive Fireball is probably kicking up some 1d-2 frags.

Also in DF I treat the Explosive spells as FAEs with the better range divisor as a House Rule.

In DF, as well, even 1 point of damage from an explosion will be effective crowd control with the Minion rules.

Good points. For big booms, "incidental" fragmentation can be trees and telephone poles.

Also, David Pulver suggested the same FAE rule (in an email) as you did, so you're in good company.

As a simplification, you could rule that all minions within the blast range of the explosion (using the FAE rule, 3xdice of damage, in yards; RAW is 2x dice) must make a fright check and potentially suffer the consequences.

A fright check seems redundant,since they are already defeated by the minion rule. Also isn't a morale check reaction roll more appropriate here?

I have an unpublished article that covers morale for units of NPCs and addresses the actual disposition of defeated minion/mook/cannon fodder NPCs after the battle. I am pretty sure that you have a copy of the draft.